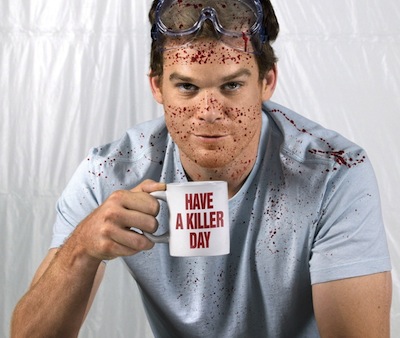

Dexter: The Simpatico Psychopath

DEXTER, Showtime’s top-rated and award-winning TV show about a Miami forensic technician leading a double life as a serial killer, ran for eight seasons between 2006 and 2013. The first season was based on the characters and plot of Jeff Lindsay’s novel Darkly Dreaming Dexter, although it adopted a less comic tone. Subsequent seasons of Dexter on television followed different plot trajectories to the book sequels, leading to Dexter’s final departure from the scenes of his crimes in Miami at the end of Season Eight.

Previously, On Dexter...

Crime writer Jeff Lindsay wanted to do something different with his original 2004 novel, Darkly Dreaming Dexter. Instead of putting a detective at the center of his procedural thriller, he chose to make a psychopath his protagonist. Anti-heroes are nothing new, especially in noir, and many a fictional detective has been little more than a psychopath with a badge – Jack Reacher, Joe Hunter, Pete Bondurant – but Dexter Morgan represents a more clinical approach.

Self-aware, controlled, methodical and secretive, Dexter leads a rigidly partitioned life, free of blind rages or drunken jags where he might beat a man to death. Dexter has no guilt, no regrets. Whereas other fictional psychopaths struggle with their murderous side, Dexter owns his, even giving it a name: Dark Passenger.

Dexter works for the Miami-Dade Police Department by day as a lowly forensic blood spatter pattern analyst. In both halves of his personality he's a hunter, following clues, solving problems, honing in on a target.By night, he gives his Dark Passenger free rein and hunts murderers, rapists, pedophiles and any other violent criminals he believes have escaped more conventional justice.

The Dark Passenger’s modus operandi is simple. He stalks his prey, captures them, drugs them, then takes them to a forensically sterile kill room where he has one final conversation about their past misdeeds (often confronting them with photographs of their victims) before stabbing them in the heart. Then, after making a slide from a single drop of blood as his trophy, he dumps the bodies far out to sea. He uses his forensic knowhow (and privileged position within Homicide Division) to ensure there’s no trail of evidence – if his crimes are discovered at all.

When we first meet Dexter, he’s been operating his dual life successfully for years, thanks to the Code of Ethics instilled into him by his now-dead father, Harry. Harry adopted Dexter at a young age, having discovered the boy at a crime scene, covered in his mother’s blood, the only witness to her brutal murder. Such a traumatic beginning might cause all manner of psychological damage, and Harry realizes, by the time the boy hits his teens, that he has the instincts of a killer. It’s only a matter of time before he commits his first murder. So, instead of attempting to enforce the impossible, or condemning his son to a life in prison, or the electric chair, Harry schools him in the art of the vigilante. If you’re careful, pick the right victims, and cover your tracks, homicide can be a fulfilling hobby rather than a capital crime.

Absolved of blame – he is not at fault as long as he sticks to Harry’s Code – Dexter kills without compunction. Within the moral vacuum of modern-day Miami, he creates his own set of values. To enforce them, he is judge, jury and executioner. He takes great pride in his work, in his ability to out-think and out-maneuver his opponents, who have in turn out-thought and out-maneuvered regular law enforcement. He considers himself superior to both his victims and is audience – us, hanging on his every word of explanation and interpretation. He is Nietzsche’s Übermensch, a Beyond-Human.

Lindsay presents Dexter as an outsider, as not quite human thanks to his lack of emotion:

“Whatever made me the way I am left me hollow, empty inside, unable to feel. It doesn’t seem like a big deal. I’m quite sure most people fake an awful lot of everyday human contact. I just fake all of it. I fake it very well, and the feelings are never there.”

Unfettered by feelings such as empathy, loss, guilt, anxiety or reproach, Dexter manages to pass as charming, sociable and polite to the people he encounters. Unfortunately, he can’t fool domestic pets about his true nature.

“Animals hate me. I bought a dog once; it barked and howled – at me – in a non-stop no-mind fury for two days before I had to get rid of it. I tried a turtle. I touched it once and it wouldn’t come out of its shell again, and after a few days of that it died. Rather than see me or have me touch it again, it died.”

He’s fully cognizant of his Otherness, his fatal difference, but it’s no big deal. He simply shrugs his shoulders self-deprecatingly and carries on. He knows the risks posed by his lifestyle, but is committed to continuing until the day he cannot. And he knows how harshly his actions – so reasonable and rational within his personal moral framework – will be ultimately be judged by outsiders.

“If I am ever careless enough to be caught, they will say I am a sociopathic monster, a sick and twisted demon who is not even human, and they will probably send me to die in Old Sparky with a smug self-righteous glow.”

Both the TV and novel narratives take us inside Dexter’s head, where he mediates events as they unfold with his running commentary on human foibles. His unfiltered observations are astute, witty and callous. Dexter’s mind keeps an ironic distance from the brutal acts perpetrated by his hands – and gives us permission to keep our distance too. To read or watch a Dexter narrative is to view the world from the cold-eyed and calculating perspective of a serial killer.

This was always going to be problematic, especially when packaged as a primetime cable TV show. As seen on screen, Dexter is a powerful, attractive individual, muscled, stronger than his victims, irresistible to a series of beautiful women. He lives an enviable lifestyle with a beachfront apartment, car, boat, enough disposable income to indulge in all the kit and caboodle required for his homicidal hobby. He has a fulfilling job, surrounded by a good-looking team of ethnically diverse individuals who accept him at face value, a typical TV workplace fantasy (see also: Bones).

Additionally, he has the luck of the Devil, teetering on the brink of discovery for end-of-episode cliffhanger after end-of-episode cliffhanger, but always managing to escape through some quirk of circumstance or plot hole before the audience tunes in the next time. He’s Übermensch as an everyday super-hero, performing mental and physical feats with ease.

The books, despite the immersive first person narrative, permit the reader to keep a certain distance from Dexter, just as he keeps his distance from his supposed friends and family. He’s an unreliable narrator on occasion. He says some outrageous things. He talks down to us, bad-mouths humans. He’s not to be trusted. He commits cold, pre-meditated murder, but the reader is given the space not to condone these acts. Dexter entertains us, but remains dangerous, a feral creature we can admire, but whose lone-wolf lifestyle we would not want to emulate.

The TV show sanitizes the less-palatable aspects of Dexter’s psychopathy. He’s the star. All other characters rotate around him – he drives the narrative. He has to win every battle for there to be another episode, another season, for the audience to keep tuning in and keep the subscription and advertising dollars rolling into Showtime’s coffers. His voice over is engaging, charming, witty, and very intimate. Dexter spills his innermost secrets into this ongoing interior monologue. He's flirting with us. This makes the audience into his confidantes, his accomplices before, during and after the fact. We sympathize with his unsated longings, we understand his need to kill, we sanction whatever it is he is going to do next. We become Dexters.

For millions of viewers, that’s an enjoyable fiction, a snarky fantasy about vigilante justice played out in a safe space on screen. For a few, however, Dexter has proved to be a dangerous role model, providing them with a convenient philosophy of murder, an icon to aspire to. Whether these copycats would have become killers without ever seeing an episode of Dexter on TV is very much open to question. What’s not in doubt is that they used Dexter as a text to justify, rationalize and explain their crimes, and, in some way, to deflect responsibility.

Dexter Copycat Murder #1: Mark Twitchell

“It's horrifying to entertain the notion that something you did inspired that…" Michael C. Hall

Canadian Mark Twitchell was convicted of first-degree murder in 2011. A lifelong fanboy, obsessed with pop culture, he fancied himself as a supervillain, thanks something he referred to as his “Genius Savant Power”. Inspired by media texts such as Star Wars (his personalized license plate read DRK JEDI) and Dexter, he had big dreams about making his mark on the world. After a crude attempt at film-making failed to spark a sensation, he decided to try his hand at serial killing in October 2008.

His modus operandi was fairly straightforward, and lifted many motifs from his favorite TV killer, Dexter. His plan was to pose as an attractive woman on the dating website plentyoffish, and lure potential victims to a lock-up garage in Edmonton, looking for casual sex. Once inside the garage, the victim would be faced by a masked Twitchell wielding a taser. After regaining consciousness, the victim would find themselves incapacitated in a special “kill room”, where they would be quizzed about bank accounts, property, emails and other key items of personal information, before being stabbed in the heart. Twitchell planned to use the information thus gleaned to maintain the victim’s existence online, thus blurring the date of disappearance and covering his tracks.

In his ‘SK Confessions’ murder manifesto (later retrieved from his computer by police and used as evidence against him) Twitchell echoed Dexter’s outlook. Like Dexter, he acknowledged his dark passenger as setting him apart from other people.

"Most people fantasize and it only ever stays a fantasy. They don't have the disposition or the stomach to go all the way with their dark urges. But I do."

He also believed his superior intelligence made him able to select victims in a rational and justifiable manner.

"I do not have any reservations about disposing of the negative people in this world who deserve a one-way ticket to the afterlife, if such a thing exists."

Twitchell’s first victim, Gilles Tetreault, struggled with his attacker and escaped, without reporting his weird experience to police. Murder is harder than it looks on TV. A week later, on October 18th, 2008, Johnny Altinger wasn’t so lucky. Twitchell lured him inside the garage, hit him over the head with a pipe, and then stabbed him in the heart. Twitchell dismembered the body (allegedly playing with the parts) and disposed of the bits into the sewer system.

Twitchell recorded his account of the crimes along with a grandiose vision of himself as a successful serial killer in the ‘SK Confessions’ document. However, his “Genius Savant Power” was not as potent as he believed it to be. Far from being a criminal mastermind, Twitchell made a number of very elementary mistakes. Altinger had told his friends where he was going to meet his online date, the garage Twitchell had rented in his own name. Twitchell also kept Altinger’s car, and told the police a ridiculous story about buying it for $40 from a tattooed man. Twitchell was soon arrested and charged with Altinger’s murder, and linked to the attempted murder of Tetreault.

The trial was a media sensation, thanks to the lurid details contained in the ‘SKI Confessions’ document (which Twitchell tried to pass off as elaborate and artistic fiction), and the easy headline links to Twitchell’s obsession with Dexter. The Altinger murder was quickly dubbed a “copycat crime”.

This shocked the producers and stars of the TV show, although Melissa Rosenberg, the original writer and executive producer, confessed it wasn’t entirely surprising. She told a reporter from CanWest News Service that a fear of copycats had been with the show since its inception. “The executive producers were expecting it. They were ready for it. They thought we were going to get slams.” However, she insisted that the show’s ethos was not about glorifying the act of murder.

“Every time you think you’re identifying with Dexter and rooting for him, for us it’s about turning that back on you and saying: ‘You may think that he’s doing good, but he’s a monster. He’s killing because he’s a monster.’”

In an interview with Jian Ghomeshi on CBC arts program Q, the actor who portrays Dexter, Michael C. Hall, expressed horror at the crimes, but didn’t think the show could be blamed for Twitchell’s behavior:

"I don't think it is a primer on serial killing or it advocates the lifestyle. I would hope that people's appreciation was more than some sort of fetishization with the kill scenes… I wouldn't stop making 'Dexter' because someone was fascinated by it only in that way. I try to tell myself that their fixated nature would have done it one way or the other.”

It’s impossible to say whether Twitchell would have become a killer if he’d never seen a single episode of Dexter and stuck with his ‘dark Jedi’ fantasies instead. Nonetheless, Dexter gave Twitchell form and structure for his murderous desires, and, in the eyes of the world’s media, elevated a clumsy, amateurish killing into a pop culture phenomenon. Without the Dexter connection, Twitchell’s trial and conviction would have been a minor, local affair, instead of inspiring news stories around the world and a book about the case, The Devil's Cinema: The Untold Story Behind Mark Twitchell's Kill Room. Through his obsession with Dexter, Twitchell has achieved lasting infamy, which, given the narcissism of his ‘S.K. Confessions’, may have been his primary aim all along. Even his viewing choices within his jail cell (subsequent seasons of Dexter…) continue to attract media attention.

Further Links on Twitchell

- Excerpts from SKConfessions (Twitchell's alleged diary) Edmonton Sun

- Glorifying A Serial Killer - Commentary Magazine

- Dexter producer stunned by news of Edmonton killing - CanWest News Service

- Michael C. Hall, 'Dexter' Star Horrified By Mark Twitchell Case, Convicted Killer Who Took Inspiration From Show - HuffPost Alberta

- Mark Twitchell, Dexter Killer, In Prison Watching The Show That Inspired Him To Kill - HuffPost Alberta

Dexter Copycat Murder #2: Andrew Conley

On November 28, 2009, seventeen year-old Andrew Conley turned himself in to police in Rising Sun, Indiana, telling them he had strangled his ten year old brother, Conner, with his bare hands, then disposed of the body in the woods the previous evening. That morning, he contemplated killing his sleeping father with a knife, but didn’t act on his impulse.

Conley was clearly a troubled individual with a history of psychiatric illness and neglect. An admitted self-harmer, he battled depression and had attempted suicide more than once. Yet the interviewing police officer, seasoned veteran Detective Tom Baxter couldn’t believe how blank-faced Conley was when describing the death of his little brother.

“I don't know how you could commit a crime like that and not be emotional about it… No tears. Just an explanation."

Although he couldn’t express why he killed his brother, Conley talked frankly about his identification with Dexter (“I feel just like him”). Like Dexter, he claimed he was in thrall to his dark side, he had a fundamental need to kill that had to be satisfied.

"Like I had to…like when people have something like they are hungry and there is a hamburger sitting there and they knew they had to have it and I was sitting there and it just happened."

Once again, without the Dexter connection, Conley’s motiveless malignity wasn’t much of a news narrative, merely a horrific one-off act. Yet media outlets pounced on the teenager’s comments about his favorite TV show, as they amplified the news values of the story. Rather than blaming Conley’s behavior on a complex set of reasons ranging from genetics to the failure of social services to a lifetime of exposure to violence as a solution to problems to the wrong psychological triggers being pressed during a sibling wrestling match, it was much easier to point the finger at the violent character Conley identified with on TV.

Further Links on Conley

- Teen Kills Brother, Loves TV Show 'Dexter': Life Imitating Art? – ABC News

- Conner Conley, 10, Allegedly Beaten to Death by His 17-Year-Old Brother – True Crime Report

Further Reading On Dexter

- An Interview With Jeff Lindsay

- Narcissists, Psychopaths And Other Bad Guys –Psychology Today

- Murders and Acquisitions: Representations of the Serial Killer in Popular Culture

– edited by Alzena MacDonald