The history of pop music is linked to the history of the technology that delivers it. Over the past couple of centuries, new technologies have enabled artists and songwriters to reach new and bigger audiences with their music, first with the single, basic unit of one song, then with album collections and, ultimately, videos straight to their phones via the internet.

If we stick with the definition that popular music has wide appeal and mass distribution, then the history really begins with the publication of sheet music — this makes pop music another media form that owes its origins to Gutenberg's printing press. Printed sheet music allowed individuals who were not the original composer of a song (or a musician lucky enough to be given a hand-copied version of the original score) to take away the music, and perform it to the audience of their choice. Songs could cross from city to city, country to country, enjoyed and played by large numbers of people at the same time.

This really took off in the 19th century, thanks to the increase in performance spaces such as salons and music halls, and touring shows. A popular singer could introduce a song to a wide audience through public performances (see Champagne Charlie, right, "as sung with great success by Miss Ada Webb"). The only way for people to hear the song again, at home, was to buy the sheet music and play it themselves. The sale of sheet music provided a small amount of income for songwriters, and forms the basis of the song publishing rights that are still part of artist contracts today. As sheet music became more lucrative (with the introduction of music playback devices, from 1885 onwards), music publishers congregated in an area of Manhattan known as Tin Pan Alley. It was so called because of the constant clatter of the resident pianists banging out songs so the publishers could hear them and estimate the probability of one being a hit. Tin Pan Alley remained the center of the American music business until the 1950s, and is still occasionally used as a term to describe the US record industry.

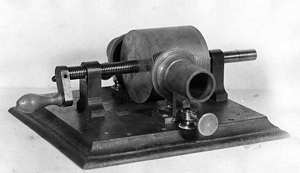

The first known recording of a human voice comes from France, in 1860, courtesy of Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville's phonautogram device.

Scott de Martinville's goal was only to find a way of "writing" sound, so that he could see things like pitch and frequency. There was no intention at the time of creating a device that could play sounds back. The first major development in this direction, was the 'player piano'. operated by a punched roll of paper that rotated and sent instructions to the specially designed piano keys.

These instruments were hugely popular from their first appearance in 1876, and can still be found as novelties around the world.

Cylinders were followed by cheaper discs (which could not be recorded on, but delivered around 4 minutes of sound) developed by Emile Berliner in the 1890s. This led to the first 'format wars', and, by 1910, Berliner's gramophone records appeared to have won. Music lovers traded in their old cylinders and phonographs for the newer gramophones, with better sound quality and a more durable product. These machines were purely for listening to music. During the early years of music playback, the companies who held patents on the various devices also tended to be the ones producing cylinders or discs. In the 1900s, this included Edison, Victor and Columbia. However, once the disc format triumphed over cylinders, and patents relating to disc-playing equipment expired, new companies set up business just to manufacture and sell records in the new '78' format. While the biggest producers were still tied to companies who made playback machines (which were still an expensive item to purchase), independent record companies started to spring up, often focusing on a specific type of music, like jazz or blues, and selling discs for a relatively low unit price.

The 10" or 12" discs that replaced cylinders were made of shellac, a substance that withstood many more plays than a wax cylinder, and which was designed to be rotated at 78 revolutions per minute for the music to sound as it did when it was originally recorded. These disks were easily manufactured, shipped and stored, and became a profitable business venture as a result. The earliest gramophones were designed to be hand cranked, winding up a spring motor which then wound itself down, spinning the disk. This meant there was some variation in the speed of playback, although this was solved with the introduction of electronic motors. As '78's were much more durable than wax cylinders, many of them have survived into the 21st century and we can still listen to them today - modern turntables sometimes have a 78rpm playback speed.

Before 1925, musicians sang and played into a horn connected to a diaphragm which in turn vibrated and moved a needle to etch a disk. This was known as acoustic recording, and it was difficult to get the mix of instruments right, and often recordings were very faint. Then came electronic recording, where sounds were captured by a microphone, amplified, and then recorded. This produced a much clearer sound, as instruments could be picked up at a wider range of frequencies and volumes, and listening to an electronically recorded 78 was much more akin to being in the same room as the musicians.

This improved recording technology ushered in the first true recording stars, and nurtured new types of music. Jazz came out of the south, east, and mid-west of the USA, where it originated in the 1890s. Like most of the popular music that was to follow, Jazz was a hybrid of everything that came before. The primarily black musicians combined musical rhythms from their African and Caribbean heritage with the strings, piano and brass of Italian operetta, ragtime syncopation and the soulful riffs of blues music. Soon, musicians of every colour were appropriating the new sounds and rhythms and making them their own. Early jazz stars include musicians like Bessie Smith, Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Bix Biederbecke and Louis Armstrong who made a name for themselves based on sales of their recordings as well as live performances.

Jazz (in the form of easily portable 78s) swept across the United States during the early years of the twentieth century, and soldiers took it to Europe as a form of popular entertainment when they were shipped there for the First World War. Then came the 'Roaring Twenties', and jazz became more than a genre of music, it became a way of life. From its beginnings, jazz was looked down upon by the white establishment as a form of low-class entertainment, associated with immorality (sex, alcohol, drugs, dancing) as well as young people. It was seen as threatening established cultural values through its promotion of inter-racial good times, and the way it provided a soundtrack for speakeasies, gangster shootouts and those scandalous dances performed by young women in skimpy clothing, the Charleston and the Black Bottom. Jazz both symbolized and was blamed for the moral degeneration of a nation's youth.

Musical performances (both live and from recordings) formed part of experimental radio broadcasts from 1906 onwards, but it was not until the 1920s, with the availability of commercial broadcast licenses in the US, and the licensing of the BBC in the UK, that music via radio became a part of home entertainment. The first radios had to be listened to via headphones, but by the end of 1920s most sets had speakers. This meant one set could be the focus of a family group, or sets (often home-made) could be listened to by individuals.

Musically, the Jazz Age faded into the Swing Era, with music that was more rhythmic, and relied more heavily on horn and percussion sections than the strings and piano used in jazz. The big stars weren't solo performers, but bandleaders such as Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw. The Charleston made way for even more frenzied dancing in the form of Lindy Hop, a fusion of many different types of jazz dance. It originated in Harlem, New York in the late 1920s and caught on quickly. Although it began with black dancers, Lindy (which is also known as Jitterbug, after a Cab Calloway song) became very popular with whites, who demanded to learn the moves. By the 1940s, it was no longer associated with one race or another. Modern Swing revived the form in the 1980s, and there are dedicated dance clubs around the world today.

A direct descendant of the automatic piano, automated record players that could hold 8-10 records, allowing customers to pick a song at the drop of a coin, were first introduced in 1927. These evolved into machines which became known as jukeboxes (after the "juke", or shady, joints where they were often found). Cafes, bars, military barracks, laundromats and pubs installed them as an easy and cheap way of keeping their customers entertained. A jukebox could be located anywhere groups of people gathered. Their sleek lines and flashing lights provided a futuristic focus to any otherwise ordinary hangout, and they drew young customers, anxious to listen and dance to the latest tunes away from a crowded family home and parental supervision. One of the most familiar and iconic designs was the Wurlitzer 1015 introduced in 1946, and known as the Bubbler (see right). These are collectors items today.

By the 1940s the jukebox was an important part of music consumption and distribution. Radio stations were wary of playing music identified as young, or innovative, or potentially controversial, so the best place to hear the newest sounds was via the latest arrivals at the jukebox. Each jukebox had a song popularity counter that registered how many times each record was played. Unpopular records were replaced quickly, creating a constant turnover of songs. The music industry kept track of changing tastes and demand via a "Most Played In Jukeboxes" chart, one of the precursors to the Billboard Hot 100.

After the introduction of synchronous sound to the production process in 1927, it quickly became apparent that musical numbers could provide spectacular set pieces for movies. Packaging a song into a movie was a way of exporting it to a bigger audience than ever before, and the song was made more memorable by the addition of accompanying visuals, usually in the form of a dance number. Hollywood turned to remaking Broadway stage musicals, and imported a lot of Broadway stars who could sing, dance and act (unlike a lot of the silent movie era performers). Some silent movie stars (e.g. Marlene Dietrich, see clip below) managed to cross over to sound successfully, and sing songs on camera. Others had to resort to playback singers, whose more tuneful vocals were dubbed over the top of musical performances, but a good set of pipes became an important asset for any wannabe-star.

Always hungry for the next big thing, movies jumped on new musical trends and showcased new dancing styles. Musicals were shot in full colour, on lavish sets, with choreography that far surpassed anything seen before on stage - thanks largely to the innovations of Busby Berkeley who understood how to combine aerial views and close ups with the conventional wide shots of dance numbers. In China, many films made in the 1930s and 1940s were based on Chinese operas, and Bollywood also embraced the musical genre. A hit song could mean a hit movie (and vice versa) and Tin Pan Alley and the movie companies did a roaring trade. The music and movie industries have remained symbiotic ever since.

Soldiers criss-crossing the globe during World War Two took their favorite music from home with them, both as a reminder of loved ones, and as a morale booster. Thanks to the ready availability of movies, records and performers willing to entertain the troops, pop music became global like never before. Audiences across Europe and Asia were enthralled by the fast-paced jitterbug and the more stately Big Band swing, as well as embracing sentimental songs that resonated with the times (e.g. We'll Meet Again). Wartime demands, and a musicians strike in the early 1940s, meant that the big band production number became less and less practical to stage live, and individual vocalists started to become more popular as artistes. Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby (whose hit, White Christmas, from the 1942 movie Holiday Inn, became the best-selling record for the next 50 years), Peggy Lee, the Andrews Sisters, Nat "King" Cole and Sammy Davis, Jr crooned their way into hearts and homes during this period.

In the years after the War ended, two social forces gathered strength that would change popular music and its relationship with society for ever: television and teenagers.

NEXT: 1950s to the present day>>>>>>>