History of Advertising

When studying today's advertising industry, it's useful to understand the history of advertising. You can look at the GCSE pages for introductory information and links.

Early Advertising

Although word of mouth, the most basic (and still the most powerful) form of advertising has been around ever since humans started providing each other with goods and services, Advertising as a discrete form is generally agreed to have begun alongside newspapers, in the seventeenth century. Frenchman Théophraste Renaudot (Louis XIII's official physician) created a very early version of the supermarket noticeboard, a 'bureau des addresses et des rencontres'. Parisians seeking or offering jobs, or wanting to buy or sell goods, put notices at the office on Île de la Cité. So that the maximum number of people had access to this information, Renaudot created La Gazette in 1631, the first French newspaper. The personal ad was born.

In England, line advertisements in newspapers were very popular in the second half of the seventeenth century, often announcing the publication of a new book, or the opening of a new play. The Great Fire of London in 1666 was a boost to this type of advertisement, as people used newspapers in the aftermath of the fire to advertise lost & found, and changes of address. These early line ads were predominantly informative, containing descriptive, rather than persuasive language.

Let Them Drink Coffee

Advertisements were of key importance, even at this early point in their history, when it came to informing consumers about new products. Coffee is one such example. Coffee was first brewed into a drink in the Middle East, in the fifteenth century. The Arabs kept the existence of this vivifying concoction a secret,refusing to export beans(or instructions on how to grind and brew them). Legend has it that Sufi Baba Budan smuggled seven beans into India in 1570 and planted them. Coffee then spread to Italy, and throughout Europe, served at coffeehouses. The rapid spread of coffee as both a drink and a pattern of behaviour (coffeehouses became social gathering places) is in no small part due to the advertising of coffee's benefits in newspapers.

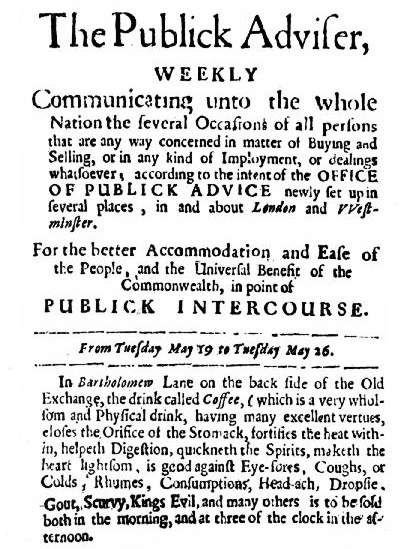

The ad to the right is the first advertisement in London for coffee, and appeared in 1657 (source: http://www.web-books.com/Classics/ON/B0/B701/15MB701.html). In Modern English, it reads:

In Bartholomew Lane on the back side of the Old Exchange, the drink called Coffee (which is a very wholesome and Physical drink, having many excellent virtues, closes the Orifice of the Stomach, fortifies the heat within, helps Digestion, quickens the Spirits, makes the heart light, is good against Eye-sores, Coughs, or Colds, Rheums, Consumptions, Head-ache, Dropsy, Gout, Scurvy, Kings Evil and many others) is to be sold both in the morning and at three o'clock in the afternoon.

This early example of advertising copy makes coffee sound like a wonder drug. While the claims in the first half of the sentence may be true (coffee does indeed stave off hunger pangs and 'quicken the Spirits'), the presentation of coffee as a cure-all for specific medical conditions like dropsy, gout and Kings Evil (scrofula - swollen abscesses in the neck) is pure advertising hyperbole. But it worked – people flocked to coffee houses to try this new beverage for themselves, and engendered a caffeine habit that persists in our society today.

Advertising and the Industrial Revolution

When goods were hand made, by local craftsmen, in small quantities, there was no need for advertising. Buyer and seller were personally known to one another, and the buyer was likely to have direct experience of the product. The buyer also had much more contact with the production process, especially for items like clothing (hand-stitched to fit) and food (assembled from simple, raw ingredients). Packaging and branding were unknown and unnecessary before the Industrial Revolution. However, once technological advances enabled the mass production of soap, china, clothing etc, the close personal links between buyer and seller were broken. Rather than selling out of their back yards to local customers, manufacturers sought markets a long way from their factories, sometimes on the other side of the world.

This created a need for advertising. Manufacturers needed to explain and recommend their products to customers whom they would never meet personally. Manufacturers, in chasing far-off markets, were beginning to compete with each other. Therefore they needed to brand their products, in order to distinguish them from one another, and create mass recommendations to support the mass production and consumption model.

Newspapers provided the ideal vehicle for this new phenomenon, advertisements. New technologies were also making newspapers cheaper, more widely available, and more frequently printed. They had more pages, so they could carry more, bigger, ads. Simple descriptions, plus prices, of products served their purpose until the mid nineteenth century, when technological advances meant that illustrations culd be added to advertising, and colour was also an option. Advertisers started to add copy under the simple headings, describing their products using persuasive prose.

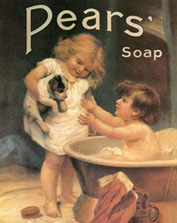

Bubbles — the Pears' Soap Advertising Innovation

However, Millais was attacked across the board for allowing his work to be sullied by association with a commercial product. Marie Corelli wrote this hysterical letter in response to seeing the ad:

Dear Sir John Millais!

...I get inwardly wrathful whenever I think of your "Bubbles" in the hands of Pears as a soap-advertisement! Gods of Olympus! – I have seen and loved the original picture, – the most exquisite and dainty child ever dreamed up, with the air of a baby Poet as well as of a small angel – and I look upon all Pears' "posters", as gross libels both of your work and you! [...] "Bubbles" should hang beside Sir Joshua's "Age of Innocence" in the National Gallery where the poor people could go and see it with the veneration that befits all great art. (Corelli, "To John Millais", 24 Dec. 1895)

Thus began the opposition between advertising, and Art.

The First Advertising Agencies

However, it was not until the emergence of advertising agencies in the latter part of the nineteenth century that advertising became a fully fledged institution, with its own ways of working, and with its own creative values. These agencies were a response to an increasingly crowded marketplace, where manufacturers were realising that promotion of their products was vital if they were to survive. They sold themselves as experts in communication to their clients - who were then left to get on with the business of manufacturing. Copywriters emerged who – for a fee – would craft a series of promotional statements. Many of these men were aspiring novelists, or journalists, who discovered they could more profitably turn their wordcraft to the services of sales – John E. Powers was reportedly earning the vast sum of US$100 per day writing copy in the 1890s. They joined forces with professional illustrators who began to produce designs specifically for the purpose of an advertisment.

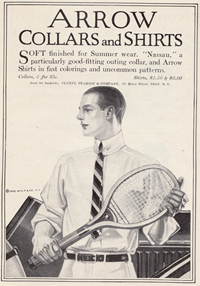

A good early example of this is the advertising produced for Arrow Shirts by the copywriting team of Earnest Calkins and Ralph Holden, who hired Joseph Leyendecker to create an image for the campaign. Leyendecker used his real-life partner Charles Beach as the model, and created a character who wasn't so much about shirts as a whole lifestyle. Suave, crisply coiffed, impeccably turned out in a sharply creased collar, the Arrow Shirt Man represented a whole set of aspirational choices for the target audience, and formed the basis of Arrow Shirt's advertising for the next quarter century.

Innovators like Claude Hopkins and Albert Lasker developed the scope and sophistication of advertising in the early years of the twentieth century. Unlike his predecessors, Hopkins was a great believer in learning all about the product he was meant to be selling. He used the fact that Schlitz Beer steam cleaned its bottles to promote the brand - notwithstanding that this was common practice amongst breweries at the time. However, through association by advertising, Schlitz became the brand associated with good hygiene and purity. While Hopkins became an expert in the products he was selling, Lasker focused on the target audience, closely monitoring ad campaigns against sales curves.

Advertising and the First World War

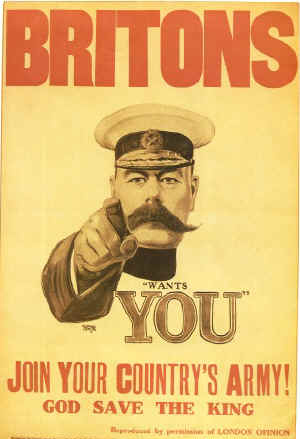

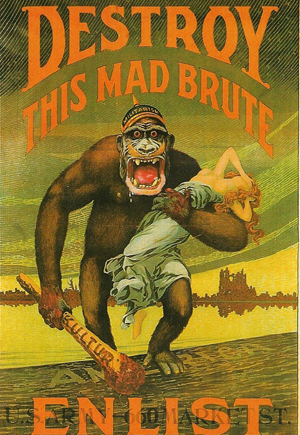

Poster advertising was much more common in Europe than the US before 1914. From the 1870s on, French roadsides were adorned with cheaply printed Art Nouveau lithographs, advertising, among other things, the Folies-Bergère Cabaret, and Lefèvre Utile biscuits. The suffragettes in Britain used a series of art posters to publicise their cause. When war broke out, all the various governments involved turned to posters as propaganda. The main requirement of fighting in World War I was young men to use as cannon fodder. The 'ENLIST!' posters dreamed up by advertising agencies on both sides of the Atlantic ensured a plentiful supply of recruits.

No less a political commentator than Hitler concluded (in Mein Kampf) that Germany lost the war because it lost the propaganda battle: he did not make the same mistake when it was his turn. One of the other consequences of World War I was the increased mechanisation of industry – and increased costs which had to be paid for somehow: hence the desire to create need in the consumer which begins to dominate advertising from the 1920s onward.

Advertising Through The Great Depression

Post war affluence and optimism was short and sweet. Spurred by the introduction of "hire purchase" agreements, consumers treated themselves to costly new goods such as cars, washing machines, and radiograms, which all needed ads. Advertising quickly took advantage of the new mass media, using cinema, and to a much greater extent, radio, to transmit commercial messages to a widespread audience. The first radio ad appeared in 1922, and, because direct selling was not permitted, broadcast a 'direct indirect' message about the benefits of living in a particular development in Jackson Heights, New York.

- Radio Commercials from 1920s-40s —Old Time Radio

The public had an appetite for radio, but there was no real way to get them to pay directly for the costly broadcasts. Advertising stepped in as the middle component, paying the broadcasters for their listeners' time. This arrangement led to the direct funding of radio dramas by, for instance, Proctor & Gamble, hence the term 'soap opera'. However, when the Wall St. stock market crashed in 1929, the media landscape changed forever.

Hard-hit consumers cut back on newspapers and listened to the radio in even greater numbers. Cash-strapped newspapers and magazine owners put their publications up for sale, only to see them absorbed into the developing news conglomerates. Cinema attendance remained buoyant - picture palaces offered the only avenue of escapism in the economic gloom. The tide of advertising dollars that had flowed into print publications stemmed considerably, and then started to turn in other directions.

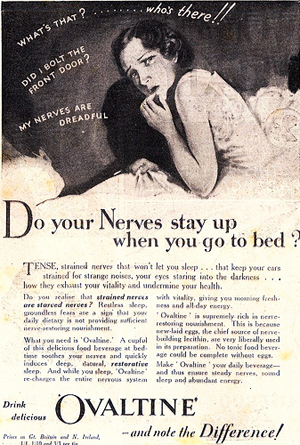

Advertising spending plummeted by around 60% after the Crash, and didn't return to 1920s levels until the early 1950s - although radio advertising spend did increase significantly in this period. Ad agencies were hard hit, often having to downsize considerably as the clients dried up. Perhaps as a result of this, advertising got tougher. By the mid-1930s, the 'hard sell' had become commonplace, with sex, violence and threats creeping into ads. Items were marketed as necessities, rather than luxuries, with items like hats or mouthwash positioned as vital tools in the battle to get, and stay, ahead. Rather than reassuring consumers, ads bullied and hustled, playing on fears in order to attach their target audience's sparse disposable income to their brand.

One agency that thrived during the Depression was Young & Rubicam. They focused on research and facts, investigating the impact of successful and failed campaigns. In 1932, agency head Raymond Rubicam hired an academic named George Gallup as the first ever market research director in adland. Gallup developed a lot of the techniques still used today to find out which ads work and why - questionnaires, focus groups, listeners' panels - as well as devising audience measurement techniques (the coincidental method for radio, and the impact method for print and TV).

Advertising & TV

The 1950s not only brought postwar affluence to the average citizen but whole new glut of material goods for which need had to be created. Not least of these was the television set. In America it quickly became the hottest consumer property - no home could be without one. And where the sets went, the advertisers followed, spilling fantasies about better living through buying across the hearthrug in millions of American homes. The UK and Europe, with government controlled broadcasting, were a decade or so behind America in allowing commercial TV stations to take to the air, and still have tighter controls on sponsorship and the amount of editorial control advertisers can have in a programme. This is the result of some notable scandals in the US, where sponsors interfered in the content and outcome of quiz shows in order to make their product seem, by association, more sexy. See the excellent Quiz Show (1994), directed by Robert Redford which deals with the disillusionment of the American people.

Unhappy with the ethical compromise of the single-sponsor show, NBC executive Sylvester Weaver came up with the idea of selling not whole shows to advertisers, but separate, small blocks of broadcast time. Several different advertisers could buy time within one show, and therefore the content of the show would move out of the control of a single advertiser - rather like a print magazine. This became known as the magazine concept, or participation advertising, as it allowed a whole variety of advertisers to access the audience of a single TV show. Thus the 'commercial break' as we know it was born.

Madison Avenue - how the Mad Men came to be

Although advertising agencies had begun to flock to offices in Madison Avenue, New York, before the war, it was only in the heady days of post-war prosperity that this street became the de facto headquarters of the US advertising industry. A lot of new, 20+ storey office buildings were constructed there in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and these prestigious skyrise workspaces attracted agencies who wanted to exude glamour and panache, and take advantage of all the fine restaurants that thronged the street level.

By the 1950s, advertising was considered a profession in its own right, not just the remit of failed newspapermen or poets. It attracted both men and women who wanted the thrill of using their creativity to make some serious cash. Hard-working (early heart attacks were common), hard drinking (those legendary three martini lunches), unconventional and often amoral, the flannel-suited Ad Man became a recognisable archetype, the epitome of a new kind of cool. Cary Grant even played one in North By Northwest (1959). For many, Englishman David Ogilvy embodied this quintessential type. He started his own ad agency, and from the very beginning, parlayed his charm and personality into the agency brand, using his British accent to stand out from the crowd.

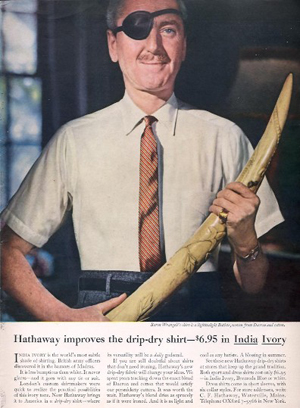

Ogilvy's advertising ethos involved bold creativity and risk-taking, but he understood that advertising's main - indeed, only - function, was to sell. To that end copy and pictures had to be clear, simple, and provide a direct connection between customer and brand. He specialized, in the early days, in attention-grabbing campaigns that relied on a clever idea rather than a huge budget. One of his earliest, most successful campaigns was for Hathaway Shirts. Like the Arrow Shirts team almost half a century before, he latched onto an image that suggested a lifestyle, rather than just a clean collar. He added a rakish eyepatch to the model (and to 25 years of subsequent Hathaway models and the logo to this day), he intrigued the audience, who would then read the copy to find out what was going on. Hooked. The 'Hathaway man' appeared in a variety of scenarios (buying a Renoir, at the Opera, driving a tractor etc), and was in fact Baron George Wrangell, a Russian aristocrat with 20/20 vision. Ogilvy only ran the ads in The New Yorker magazine, adding to their allure. The Hathaway brand became the #1 best-selling dress shirt in the world.

Much has been written about David Ogilvy, especially as he was one of the first ad men to recognize that if you create a story around an ad campaign, you're getting a lot of free advertising. He made his agency part of the story-telling process of a campaign. Although he disliked the label, Ogilvy was hailed as a genius in his day, and more than a decade after his death, is still very much considered a guru of modern advertising.

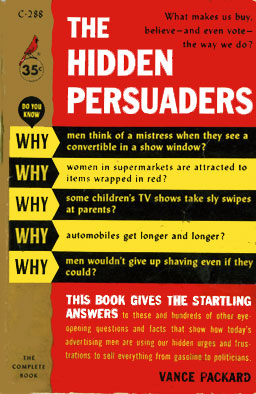

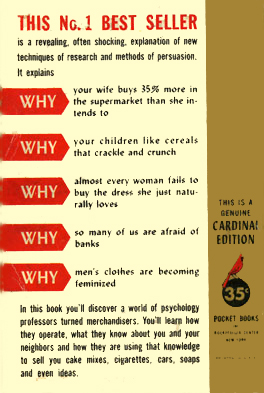

However, not all the ad industry archetypes being generated in Madison Avenue in the 1950s were positive ones. In 1957, sociologist Vince Packard published his exposé of the advertising industry, The Hidden Persuaders. Packard accused the entire ad industry of psychologically manipulating the public into buying products they didn't want or need, usually via embedded or subliminal messages in ads and images. He also suggested these techniques were being imported into politics, and were used to persuade voters to accept politicians and policies they would otherwise have objected to. As a conspiracy theory, it convinced, especially given the Cold War paranoia of the era. People were used to the concept of 'the enemy within', on the alert for subtle Communist propaganda, leery of the concept of mind control. The Hidden Persuaders became a best-seller, and has coloured attitudes towards the advertising industry – painting them as villains, out to exploit and brainwash the public – ever since.

Recommended Reading

Other Useful Links

- Emergence of Advertising in America 1850 - 1920 - A historical overview of the images

- Ad Access - superb collection of American print ads 1911-1955

- AdFlip - huge archive of print advertising

- Fifty Years of Coca-Cola Advertisements

- History of Advertising Graphics - a look back at the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries