Television waved farewell to two of its iconic anti-heroes over the past week: Walter White and Dexter Morgan. Although these characters were worlds apart in style and execution, at their core they both embodied the essential oppositions of the anti-hero. After eight seasons each, they will be missed, albeit for different reasons.

The anti-hero is a compelling character type within fiction. On one level, he or she is a subversion of the traditional hero, devoid of the typically heroic qualities of loyalty, morality, nobility, physical strength and beauty, athletic skills, intelligence or confidence. The anti-hero is flawed — often fatally — and answers only to him or herself, and their internal values (which may not be values in the truest sense of the word). The anti-hero is the Jungian shadow of the hero, the dark untrammeled self, the cautionary tale of what happens when an individual steps outside the light.

Nonetheless, the anti-hero still gets stuff done, often in the form of revenge or payback, or vigilante justice. Unfettered by a moral framework, the anti-hero can work outside social and legal restrictions, free to act as he or she chooses. The anti-hero represents a seductive ‘What If…’ for audiences. What if you could make your own decisions? Enforce your own justice? What if nothing else mattered but gratifying your desire for vengeance?

Anti-heroes have been around in literature for a long time, lurking even in classic works (think Satan in Paradise Lost or Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair). They were pervasive enough in the opening decades of the twentieth century for the devisers of the 1930 Hays Code to take specific steps to prevent them from appearing onscreen, in the interest of protecting the morality of the masses. Only bona fide villains (those who would be punished or destroyed in the final act) could break the law. Protagonists, or those who engaged the audience’s sympathy, had to be card-carrying Good Guys or risk degrading the entire human race.

The first ‘General Principle’ of the Code is very clear:

No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.

The Code also rails against ‘Crimes Against the Law’:

These shall never be presented in such a way as to throw sympathy with the crime as against law and justice or to inspire others with a desire for imitation.

1. Murder

a. The technique of murder must be presented in a way that will not inspire imitation.

b. Brutal killings are not to be presented in detail.

c. Revenge in modern times shall not be justified.

The anti-hero, pulling sympathies in the wrong direction, providing a perverse example for imitation, vindicating vengeance, was perceived by the creators of the Code as a dangerous, destabilizing figure who, over time, could corrupt the wholesomeness of a nation.

The 1954 Comics Code also prohibited the depiction of anti-heroes, specifying:

1. Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

and

4. If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

5. Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

6. In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

These restrictions now seem quaint. We’ve moved far beyond such moral absolutism. Today’s film, comic and TV makers have zero interest in the “moral importance of entertainment”. Audiences can access any type of violent, sexual, or amoral media at the click of a button or the swipe of a screen, and take responsibility for their own corruption, or otherwise. From the 1990s onwards (especially within comics), the tendency has been for even regular heroes to be flawed, to be as much about their anger as their courage, their stories hinging on mistakes as opposed to triumphs. This is partly to do with a desire for novelty and innovation (the all-American hero schtick got old) and partly to do with a desire not to be lectured during leisure activities. We no longer need to be protected from the anti-hero — he or she is just another part of the pantheon.

Yet we still have a keen sense of the difference between hero and anti-hero. They light up different parts of our brains. Anti-hero narratives make for challenging viewing; we want the protagonist to live to fight another day, but we’re aware that the anti-hero’s continued survival isn’t necessarily a good thing. Anti-hero stories are unpredictable, as outcomes aren’t decided around the ‘good always triumphs over evil’ convention, and the characters are inconsistent, oscillating wildly, establishing unique patterns of behavior. Anti-heroes might win our sympathy with one decision, and trample it into the dirt with the next. Anti-heroes force us to re-examine our own moral values, to think about what we’re watching and how we’re reacting to it. The anti-hero occupies a rich, intensely layered and fluid narrative space. It’s no wonder anti-hero TV shows win all those fans and awards.

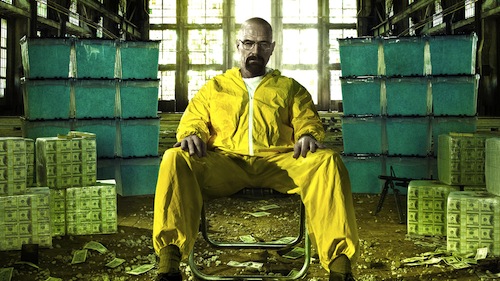

Breaking Bad dealt in relatively conventional moralities throughout Walter White’s transition from upstanding citizen to master criminal. Walt didn’t start out as an anti-hero, but instead was first represented as a victim, of bad luck, of the US health care system, of others’ greed (that shady business with Gray Matter). He became consistently less sympathetic (although no less compelling) through his eight season arc, as it gradually became apparent that Walt was the victim not of external circumstances, but of his decidedly anti-heroic ego. This meek, family-orientated, high school chemistry teacher was suppressing his inner criminal mastermind, but it took a terminal cancer diagnosis for Walt to let Heisenberg out.

Like any released genie, Heisenberg proved impossible to put back in the bottle. That’s the power of the anti-heroic track. Even after Walt had stashed millions of dollars under his house, he couldn’t stop. Once he’d switched from making decisions with a conventional moral framework (“Is this legal? Will anyone get hurt? Will I go to jail? How long for?”), and was instead relying on raw instinct and expediency (“Is this physically possible? Will this destroy my enemies? Will I survive?”) there was no going back. He had to stay the course to its bitter, anti-heroic end — his own destruction — and there was little he could do to mitigate collateral damage (especially Hank) along the way. Stripped of everything he once valued, home, family, social status, friendship, moral standing, Walt was left with nothing but the anti-hero staples (and double edged swords) of freedom, and a belief in himself: Walt’s final comment to Skyler, “I did it for me. I liked it. I was good at it and I was really – I was alive” articulates the essential anti-hero creed without excusing his villainy. While the Hays censors may have objected to the scene-by-scene content of Breaking Bad, they may have applauded its overall message: although it might be fun to begin with, in the long term Crime Does Not Pay.

Dexter Morgan, on the other hand, was an anti-hero long before we met him, comfortable in his skin as a vigilante killer and fine-artist faker of human emotions. His eight season arc ran the opposite way to Walter White, from deviancy to conformity, and was less satisfying as a result. Dexter began as a bold satire on the conventional police procedural, a crime scene investigator who used science to commit crimes, not solve them. He took advantage of his position as a forensic tech at Miami-Dade Homicide to cloak his true self as a serial killer. By day he worked as a lowly drone for law enforcement, processing case evidence, keeping the wheels of the justice system moving. By night he enforced his own law, selecting victims from those who’d escaped conventional punishment, and dealing his unique brand of justice, which involved tranquilizers, a plastic-draped kill room, and a blade through the heart.

Dexter held up a cynical mirror to the 1990s fascination with serial killers, and presented a psychopath not as a Hannibal Lecteresque monster, but as a charming, affable creature, eager to please, anxious to explain himself, logical, rational, eternally justifiable. While he was a true blue anti-hero on the inside, on the outside, Dexter was That Guy From Work who buys boxes of donuts as a way of winning at office politics.

Dexter‘s desire to blend in was comic at times, as it conflicted so drastically with his interior disdain for the rest of the human race. He considered himself in Nietzschean terms, as outside regular society but superior to it. But his Super-Man qualities proved to be flaws, rather than strengths. Like all anti-heroes, he felt isolated. Deep down, all he wanted was to hang out with others like him, those who relished murder: his brother the Ice Truck Killer, Lila, Trinity, Hannah, Zack. A lot of screen time each season was given over to the strengthening of his ongoing relationships, with his sister, his co-workers, his child, and the love of his life. As a result, Dexter traveled in the opposite direction to Walter White, away from anti-herohood towards assimilation, towards thinking about others in his decision making process, towards considering the moral consequences of his actions. He tried to put his anti-hero roots behind him and become a regular guy on the inside too.

Artistically, this proved to be the show’s downfall, as, over the final three seasons, audiences became dissatisfied at Dexter’s transformation away from lonely anti-hero outsider into a devoted lover, father and brother, a state usually reserved for conventional heroes. Given his murderous proclivities, this hardly seemed fair — even to 21st century moral relativist sensibilities. The Hays Code censors would have hated Dexter for more than its sensual depiction of murder (or lackadaisical approach to child care). While Breaking Bad never lost sight of the wider moral and social framework in which Walter White operated, Dexter blurred the lines between good and evil to suit inconsistent plot purposes. Whether you’re dealing in heroes or anti-heroes, changing the rules on a writer’s whim rarely appeals to an audience.

Even though Dexter and Walt have disappeared from view, the anti-hero remains a robust component of popular culture, providing a vigorous antidote to the dumb hero-worship of comic book adaptations. The fears of the Hays and Comic Code censors about their detrimental effect on society haven’t quite been realized — far from it. We seem to appreciate our anti-heroes more when they turn out to be governed by the same moral codes as the rest of us.

See also: