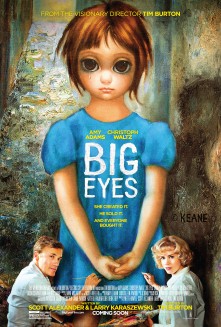

Writers: Scott Alexander, Larry Karaszewski

Stars: Amy Adams, Christoph Waltz, Krysten Ritter, Danny Huston

Everyone loves a juicy retribution story, especially on Christmas Day. Big Eyes serves up a delicious slice of injustice fought and wrongs righted, seasoned with all the whimsy of the titular paintings. Screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski (who worked with Burton on his 1994 biopic about another pop culture icon, Ed Wood) fashion Margaret’s struggle for recognition into an imaginative moral fable. Their screenplay also explores some more serious questions about art and ownership: key issues for our copyright-disregarding age.

Tim Burton tones down the quirk in favor of a colorful period piece. Margaret (Amy Adams) is an archetypal 1950s housewife who finds the courage to flee her first husband and relocate to San Francisco, gateway to the new era. The cocktail frocks are fabulous, especially those worn by Dee-Ann (Krysten Ritter), bohemian BFF. She discovers it’s hard out there for a divorcée with a child to support. Working women are frowned upon, even when they are skilled technical artists. Discouraged, broke, vulnerable, she welcomes the attentions of Walter (Christoph Waltz), a charming landscape painter/realtor, who sweeps her off her feet and back into the security of a respectable married existence. He seems like the nicest guy: attentive, charming, encouraging her to paint her distinctive portraits of big-eyed children. As a cute, artsy couple, they both sign their paintings “KEANE”. Walter, the consummate salesman, even arranges a joint exhibition of their work, her Big Eyes portraits alongside his Parisian street scenes, in a hip jazz club.

This is where trouble creeps into paradise. The first sale is one of Margaret’s waifs, not Walter’s cityscapes. When pressed by the buyer, he takes credit for the work – purely in the interests of the sale, he assures his wife who, reluctantly, lets it slide. The paintings keep selling, Walter keeps lapping up the acclaim, and Margaret is kept hidden in an attic, churning out maudlin representation after maudlin representation of her signature big-eyed child.

Big Eyes is therefore a study of domestic abuse. Walter alternately cajoles and threatens his wife into keeping their little secret, and she must even lie to her daughter about where the paintings come from. She is expected to put up and shut up. A non-Catholic, she stumbles into a confessional where a priest tells her she should obey her husband in all things. But the 1950s are over. By 1964, Margaret has tired of being downtrodden and, once again, grabs her daughter and flees her husband. This time she lands in Hawaii, where she gathers the strength to fight for what is rightfully hers.

Christoph Waltz is excellent as Walter, manifesting the monster with the same deft plausibility as the sweet talker. He takes time to seduce the audience along with Margaret, presenting the abusive husband as charmer rather than thug. In the first half of the movie he’s witty and agreeable, readily admitting to minor flaws. When he tells Margaret that, in his mind, they share creative rights to her pictures (“What’s yours is mine”), he seems motivated only by the most earnest and pure intentions. Yet, as the lie lingers and grows, the stress of perpetuating the fraud pushes him into some very dark places. Amy Adams gives him plenty to play against, turning in another nuanced and sensitive performance. Her Margaret is never a doormat, just a decent woman who realizes, too late, that there’s no easy way out of a gilded cage. She doesn’t paint because her husband tells her to, she creates because she is compelled. Her intentions are as pure as they come: she wants to share her children with the world, and she struggles to understand why her husband might exploit her talents so cruelly.

It’s a long time since Burton made a movie this intimate, although it’s easy to see what drew him to the material. Margaret Keane was an outlier, ignoring the derision of critics to paint what and how she wanted. Burton takes a few none-too–subtle jabs at illustrious members of the art establishment who dismiss popular art, like the Big Eyes prints or Burton’s candy-colored movies, as having zero merit. Jason Schwartzman cameos as a San Francisco gallery owner who sneers at Keane’s work and then can barely contain his disbelief as prints fly off the shelves. Terence Stamp, as New York Times art critic, John Canaday, also pours vitriol on the Big Eyes kitsch, denying Margaret’s talent for capturing emotion with her brush just as much as her husband ever did.

Big Eyes offers a gaudy portrait of creativity as a gift from the gods: some people have it, some people fake it, everyone wants to be loved for it. Although based on a true story, it’s a fairy tale about the power of imagination and pure artistic intention to transcend the slime of the real world.

Big Eyes opens Dec 25th.

More information (including a gallery of Big Eyes art) at http://bigeyesfilm.com/