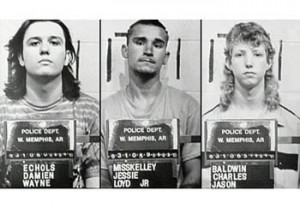

After 18 years in jail, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley have been released. While they were forced to submit guilty pleas, and accept a sentence of time already served, they are no longer moldering in prison (with Echols on Death Row) for a crime it has become clear (thanks to DNA evidence) they did not commit. They owe their freedom in no small part to documentary makers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, whose trio of Paradise Lost films argued long and hard for the boys’ innocence, and attracted moral and financial support for their cause from the likes of Eddie Vedder, Johnny Depp and Natalie Maines.

The film-makers’ persistent questions (their first film came out in 1996) about the validity of the trial, the lack of physical evidence, and the insistence that the murders were part of ‘satanic cult’ activity kept Echols clear of a lethal injection, and also kept media interest in the case alive. Alongside social media efforts (such as Free The West Memphis Three and Facebook pages supporting the trio), the exposure provided by the documentaries meant that this case didn’t go away.

The Paradise Lost films are worth examining, not just for the light they shed on one particular miscarriage of justice, but for how they show young men being demonized for their choices in music, clothing, hairstyles and reading matter, and made into scapegoats for society’s ills.

‘Fear of youth’ is well documented (in institutional rules and government edicts), and is known as ephebiphobia. It has been part of our cultures for centuries. Young people (especially young men), thanks to their strength, energy and willingness to try new ideas, are seen as a destabilising force by those who are invested in the old order. As the oldsters are the ones with all the power, they often take brutal pre-emptive and/or retributive action against perceived threats from youth (see: the Lost Boys of the FLDS). Most moral panics revolve around an aspect of youth or street culture, as authorities are persuaded by public outcry to crack down on aberrant behavior primarily from young males.

The discovery of the bodies of three eight year old boys in Robin Hood Hills, West Memphis, in May 1993, led to a moral panic that was to set the ephebiphobic aesthetic of the decade. The horrific murders were immediately attributed to a ‘satanic cult’ believed to be operating in the area, and the name of a local teenager, Damien Echols, was mentioned as a possible perpetrator.

Damien attracted suspicion, not because he had a track record of violent criminal behavior (although local police had been trying to pin all manner of crimes on him) but because he was different. In this staunchly Baptist community he had sought spiritual answers elsewhere, through Buddhism, Catholicism and Wicca. He grew his hair long, listened to Metallica, read Stephen King novels. He had also been treated for depression, and habitually wore black, including a long black coat. The local community believed that these circumstances made the unhappy and isolated young man ‘sinister’, and so the witch hunt began.

Instead of reviewing evidence dispassionately (which might have led them to one of the stepfathers of the murdered boys), the local police decided that Damien was to blame, and set about gathering gossip and hearsay that, in their eyes, could prove their case in a court of law. When solid proof of Damien’s guilt was not forthcoming, they hauled in “witnesses” who, tempted by the $30,000 reward money on offer, were happy to make up any amount of lies about what they had seen and heard. They also corralled Jessie Misskelley, an acquaintance of Damien’s. Jessie was mentally disabled, with an IQ of 72, and eventually, after much prodding from police, came up with a confession that implicated himself, Damien, and another boy, Jason Baldwin, in the murders.

Despite the gaping holes in Jessie’s confession (which he later recanted), and the lack of any substantial evidence, the local media, police and community were insistent that the boys were guilty, that they were Satanists, and that the victims had been sacrificed as part of some crazed blood ritual. Christianity is a force to be reckoned with in West Memphis, and the locals found it easier to believe that Satan was working among them (via Damien) than to confront uncomfortable questions about child abuse within the victims’ families. The crime was firmly pinned on the ‘Others’, the young, disenfranchised outsiders. The kid who had dared to be different was sentenced to death.

Throwing three innocent kids in jail didn’t solve the wider issues. The alienation felt by young American males was still there, and became an increasing part of the cultural zeitgeist, their inarticulate anger explored in movies like The Basketball Diaries, and songs like Pearl Jam’s Jeremy.

Did the songs, movies and video games of the era create monsters, or just call them out of the dark?

Luke Woodham, Kip Kinkel, Michael Carneal, Jamie Rouse, Barry Loukaitis, Colt Todd, Andrew Wurst and Evan Ramsey were all aged between 14-16 when they opened fire on parents, teachers and classmates in small towns across America during a period of just over two years (February 1996-May 1998). However, before any of these boys brought a gun to school, or wrote a note, or built a bomb, or posted on an internet bulletin board, society was already afraid of them, thanks to the specters of the West Memphis Three. The school shooters simply bought into the idea that because they were different, they were doomed. Give a dog a bad name, and he might shoot himself.

The media jumped on their perceived common traits, depicting them as a homogenous group of depressive, bedroom-dwelling, video game obsessed, grunge or metalhead, friendless losers – younger brothers to Damien Echols – and, with a national Satanic panic out of the question desperately tried to link these disaffected killers to specific media texts, rather than say, the medication many of them were taking. These boys wore black, especially in the form of long coats, as a way of expressing their otherness amongst the colorful plaid and sweats of their peers. They came to signify a national malaise, an army of Others who could pop up, guns blazing, in any high school corridor near you.

By the end of the decade, thanks to the Internet, and to the murderous actions of Klebold and Harris in Columbine, this tribe of misfits acquired a label: the Trenchcoat Mafia. The stereotyping begun with Damien Echols was set in stone, and outsider equalled killer, to be isolated and ignored, despite the fact that many of the teens who adopted the attitude and uniform of the subculture had never even handled a gun.

It’s 2011. Now Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley are free men, perhaps we should look again at the prejudices that falsely convicted them? Is it possible for us to learn from the mistakes of the past? Now, instead of demons in dusters, we have hoodie horrors; the outer layer has changed but the inner bogeyman remains the same. Adolescent males are still being ostracized and criminalized by adult society. They are forced to the fringes, denied status, affection, hope for the future, paraded as straw dogs in movies like Eden Lake, Harry Brown, even The InBetweeners. Should we be surprised when they bite back, as in London and Philadelphia recently? Will we continue to substitute stereotyping for genuine understanding?

The West Memphis Three – Comprehensive case history from TruTV Crime Library

Who Are The Trenchcoat Mafia– BBC archive from April 21st, 1999, which shows how quickly the media jumped on the term.